Regular readers of PogoWasRight.org may recall that Nomi Technology ran afoul of Section 5 of the FTC Act over statements in its privacy policy that it did not live up to. To settle charges by the FTC, they signed a consent order in April, 2015. But now they may be facing some more questions from the FTC, because researcher Chris Vickery discovered that a large database – over 9.1 terabytes – of what appears to be tracking records and consumer MAC addresses was exposed on a public server.

As part of the services it provides, Nomi generates retail store analytics that may include tracking consumers through WiFi and iBeacon sensors both in the store and as they are walking by outside the store. Nomi shifted more intensively to iBeacons after iOS8 made it impossible to identify repeat visits from customers with an iPhone from their MAC address.

Consumers may opt out of tracking by providing their MAC address on Nomi’s web site. If the consumer does not opt out, they may be tracked. It is up to stores, however, and not Nomi, to post notices informing customers about tracking and how to opt-out.

Last week, researcher Chris Vickery discovered that a Nomi MongoDB database was leaking on port 27017. A screencap from one of the directories in the leaky database provided to DataBreaches.net shows just some of the stores that might – or might not – be customers of Nomi:

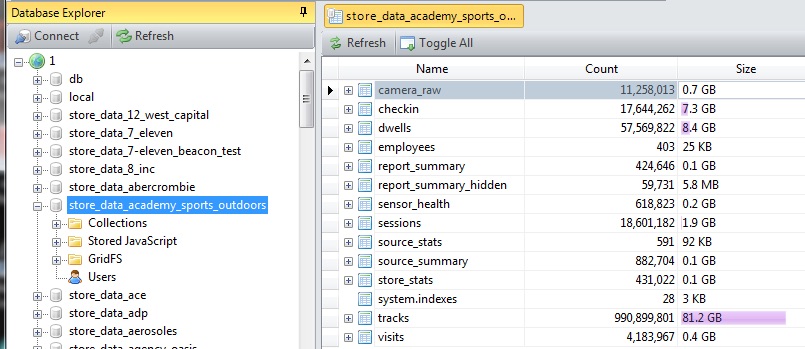

The “might not be” is an important qualifier. Some of the directory names suggest that Nomi may have been performing testing for potential clients or may have just been creating dummy data to provide a presentation to a potential client. As one example, the following screencap might suggest that Sports Academy + Outdoors is using Nomi to track:

But is Sports Academy + Outdoors a customer of Nomi’s and are the data real? It’s hard to fathom why anyone would create almost 1 million records of fake tracking data, and Sports Academy + Outdoors’ privacy policy does not mention any tracking:

Academy may gather information at its retail stores.

When you visit an Academy retail store, we may ask you for personally identifiable information to complete your purchase transaction, collect comments, enter you in a sweepstakes, or provide you with other in-store opportunities or services. All information collected in our stores is subject to the terms of this Policy.

So have they been tracking customers without mentioning that in their privacy policy because they don’t consider the tracking data and MAC addresses “personally identifiable?” Or are data in the database fake? DataBreaches.net sent an inquiry to the retailer but has received no response as yet, and Nomi did not answer certain questions DataBreaches.net put to it.

Does Nomi Live Up to Its Privacy Policy Assurances for Data Security?

Nomi’s Privacy Policy says:

We take reasonable security measures to protect your data while in transit and in storage. Data is encrypted while in transit and in storage. We hash MAC addresses before we store them, and we will not re-identify the data we collect. We retain data about individual hashed MAC addresses for 18 months, unless we have to keep the information for legal purposes. After 18 months, we only retain data about hashed MAC addresses in aggregate form.

“They are absolutely lying about the data being encrypted during storage. It’s not encrypted at all,” Vickery tells DataBreaches.net. If the data aren’t real, then that’s not a great concern. But if they are real data…?

In a statement to DataBreaches.net, Nomi claimed that the database was a “test database.” They did not respond to multiple requests for clarification as to whether this was a database with real data in a test environment or a test database populated by fake data.

If the data were real, then any MAC addresses should all have been fully hashed. Vickery informed DataBreaches.net:

Some of the MAC addresses are completely hashed, some have half the MAC address in plain text and the main string hashed. The importance of the first half is that it identifies the manufacturer. The first half isn’t universally unique, but it’s still in plain text… which is somewhat deceptive considering what Nomi has claimed about hashing everything.

Of greater concern if the data are real, Vickery noted that the MAC addresses of those who opted out were not hashed at all and were completely plaintext.

And despite Nomi’s statement in their privacy policy that after 18 months, they only retain data about hashed MAC addresses in aggregate form, Vickery found individual, unhashed MAC addresses from 2013, a sample of which he provided to DataBreaches.net. But again, were those data real?

In response to inquiries from this site, Nomi sent DataBreaches.net a statement saying that they had recently become aware that a single individual gained unauthorized access to a test database containing information related to their business clients. “Nomi does not collect or maintain any personally identifiable information regarding customers,” spokesperson Doug Benson noted.

“The security of our clients’ information is a top priority for Nomi,” he added. “After learning of the access, we immediately initiated an investigation, took the affected test database offline, and performed a comprehensive analysis of our security systems to insure there had been no other unauthorized access to the database.”

Nomi was notified of the leak by Vickery on December 9, and their CSO responded on December 10 to his notification. Despite the CSO’s request that he destroy any downloaded data, Vickery informed them that he would retain the data as proof until the FTC had a chance to investigate his complaint to them about the leak. Vickery informs DataBreaches.net that Nomi’s CSO also told him it was a “test database.”

According to the spokesperson’s statement to DataBreaches.net, Nomi is in communication with relevant state and federal authorities regarding this incident.

“We are continuing to evaluate this incident and will take any further appropriate steps necessary to protect clients’ data,” the spokesperson added.

In response to follow-up questions again seeking clarification as to whether the data were real or not, Nomi’s spokesperson responded:

We are continuing our internal investigation and are in touch with the appropriate authorities. Beyond that, we’re not in a position to make any

further comments.

What’s the Risk?

Even though Nomi claims it does not collect personally identifiable info, it’s

controversial whether MAC addresses should be considered personally identifiable information because they are persistent identifiers that could be used to determine where a person goes every day, where they work, etc. MAC addresses may be considered personally identifiable information under certain circumstances. As Sarah Gordon of the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF) explained last year in discussing the Mobile Location Code of Conduct:

However, it is important to understand, that Code does NOT take the position that hashing MAC addresses amounts to a de-identification process that fully resolves privacy concerns. According to the Code, data is only considered fully “de-identified” where it may not reasonably be used to infer information about or otherwise be linked to a particular consumer, computer, or other device. To qualify as de-identified under the Code, a company must take measures such as aggregating data, adding noise to data, or statistical sampling. These are considered to be reasonable measures that de-identify data under the Code, as long as an MLA company also publicly commits not to try to re-identify the data, and contractually prohibits downstream recipients from trying to re-identify it. To assure transparency, any company that does de-identify data in this way must describe how they do so in their privacy policy.

While Nomi’s policy appears to comply with that, the fact that the MAC addresses in the leaking database were not fully hashed in all cases raises concerns – if they were real MAC addresses.

For a more detailed discussion of the general risks of retail tracking, see Ashkan Soltani’s article from earlier this year.