When Michael Ramirez recently used Rite Aid’s mobile app to check on a prescription, he never expected to be able to access other customers’ names, addresses, and prescription records. But he was able to, and now Ramirez, a computer scientist working for the Navy’s Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command in Charleston, is going public with his concerns about Rite Aid’s response to the security problem he discovered.

Ramirez says he discovered the problem because he was checking traffic from his smartphone and saw the Rite Aid application web service exchange. “Although it does an application login, I realized very quickly that it did not use it in the web service calls nor did it establish a session. That’s when I knew something wasn’t right,” Ramirez told PHIprivacy.net.

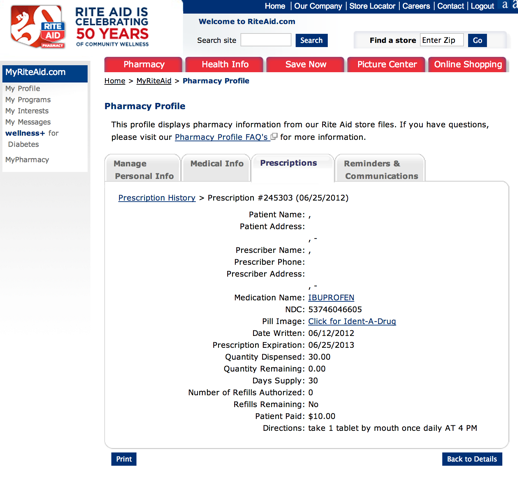

At least two of Rite Aid’s services, “RAPrescriptionHistory” and “RAPrescriptionDetails” were inadequately secured, according to Ramirez. Those services included the patient’s name, address, their doctor’s name and address, the names of their medications, and their refill history.

“The root issue is that there is no authentication that occurs,” Ramirez explained to PHIprivacy.net. “The only thing that is providing any protection is a static “username” field in the request. The system essentially uses a hard-coded password that the iPhone and Android Rite Aid applications have embedded that is easily interceptable (from discovery to first test, it literally took all of 5 minutes).”

Ramirez sent PHIprivacy.net some proof that he could access others’ data. I am not reproducing the proof here to protect the other customer’s privacy.

Although casual users of the mobile app would likely not notice or exploit the security problem, Ramirez says that anyone with some IT knowledge would recognize – and could exploit – the problem.

Ramirez was critical of Rite Aid, noting that the two services weren’t even designed to require authentication. “This should have been caught at multiple levels. In my opinion, this is far more dangerous than an oversight that would be immediately caught by any fat-fingering user; this application was either negligently or intentionally designed to provide the illusion of security. This was not a simple oversight of not having a server configured correctly – if that were the case, it’d already be fixed. This was a major corporation not following basic security practices.” It would be a trivial matter, he says, to write a script that could scoop up all of the data in the databases.

Ramirez contacted Rite Aid on September 14 to inform them of the problem, and on September 17, had a phone meeting with both Andy Palmer, Rite Aid’s Vice President, Compliance Monitoring and Robert Lautsch, Rite Aid’s Senior Director of IS Security. The meeting was productive, Ramirez says, and following their first conversation, Rite Aid took some initial steps to secure the database. “The first action they did take was to suppress the prescription details service from returning patients’ and doctors’ names and addresses. It was a good first step, but even having unfettered access to prescription history/details without the names included is still a significant security risk,” he reports.

As a second step, they began to require that both the userId and pharmacyId match correctly before returning information. “This makes it harder, but far from impossible, to still access full prescription information,” Ramirez says. “If I know the date/location where someone got their prescription filled, if I know even one of their prescription numbers, if I know any other of the unique identifiers – I can still figure out what other medications you’re on without much trouble.”

When Rite Aid asked him for a second meeting with their developers to provide his thoughts and suggestions, Ramirez agreed, but according to Ramirez, what started out well fell apart after Rite Aid’s CIO and legal counsel joined the next phone meeting. “Instead of shutting down the service and conducting a comprehensive review – as I suggested – they made marginal steps to suppress a few fields from the data set. Instead of enabling real session management or authentication – as I also suggested – they claimed that it was too difficult in the short term and requiring authentication for everything would hurt their iTunes app ratings. I wish I was making that up, but it was quite clear what the CIO was interested in,” Ramirez tells PHIprivacy.net.

Asked for their response to some of Ramirez’s specific allegations, a Rite Aid corporate spokesperson sent the following statement to PHIprivacy.net:

Rite Aid takes patient privacy and security very seriously and has a comprehensive information security program that is designed to protect patient information.

A security concern regarding our mobile app was brought to our attention. We are not aware of any personal health information being compromised as of the present date.

We continue to investigate the issue, and are working with experts in this area, SecureState Consulting LLC., and SunGard Availability Services, as well as taking other actions as necessary to ensure that such information remains protected.

Update: It just dawned on me that if Mr. Ramirez’s allegations are correct in that the app’s authentication and security were epic #FAILS, then might Rite Aid be in violation of the consent order it signed to settle the FTC’s complaint about privacy and data security for patient data in 2010?