Threat actors known as Vice Society have disclosed another attack on the healthcare sector. This time, the victim is United Health Centers of the San Joaquin Valley in California.

Lawrence Abrams of BleepingComputer reports:

On August 31st, BleepingComputer was told by a source in the cybersecurity industry that United Health Centers was reeling from a Vice Society ransomware attack that caused them to shut down their entire network.

Neither BleepingComputer nor DataBreaches.net have been able to get a response from UHC to multiple inquiries about the incident. As one consequence, DataBreaches.net has filed a public records request with the California Department of Public Health because under California law, UHC was required to notify the state within 15 days of detection of a breach.

As Abrams reports, Vice has dumped data. The dump appears to be a somewhat disorganized assortment of files. Some of them appear to be routine functions or business, but many that DataBreaches.net reviewed involved protected health information (PHI):

This site saw numerous files with insurance billing information on named patients. The files included patients’ name, date of birth, date of service, insurance policy information, and diagnostic code and/or treatment/service code. While the latter two are generally provided as numbers, those numbers can be easily looked up online to determine what a patient was being treated for or what treatment they were given. Because DataBreaches.net has previously provided images of such forms, there is no point in including yet another redacted form here.

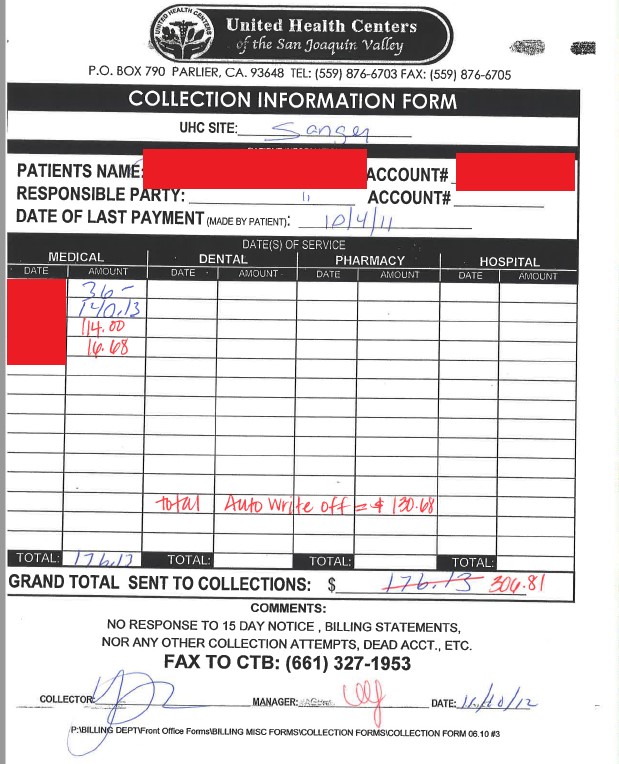

But DataBreaches.net also found a folder with what appeared to be old collections records — patients who were in arrears on their account and whose bills were sent out for collection in 2012. For each patient, there were often multiple pages of records. As but one example, the following are just two of multiple pages in a batch file on a patient whose information was sent for collection in 2012:

Note that for these two pages, there was a grand total of approximately $300 sent for collection in 2012. Other pages for this patient in the file revealed what tests and procedures the patient had and was billed for. So the protected health information now dumped on the dark web for this patient includes their name, address, date of birth, Social Security number, and additional details related to service dates and services and some clinical findings. And that’s just one of many patients whose accounts were sent to collection.

How much will it cost UHC now for their failure to adequately secure old collection accounts?

We also saw a patient roster for part of November, 2020. The roster included patient full name, date of birth, patient ID, postal address, and other details. There were more than 5,000 entries in the roster (some patients had more than one entry):

There were also files such as prescription refill forms that contained patient information and the name and dosage of prescribed medication.

The preceding is not a complete list of all types of PHI that were exposed in the data dump. DataBreaches.net is providing samples because UHC has not been forthcoming and has not issued any public notice that we can find to warn patients about what kinds of information on them is now in the wild. Of note, DataBreaches.net has not noted much data from current or recent patients, although a review of the dump has not yet been completed.

Vice Society generally claims that they dump all of the data they have exfiltrated. If that is the case here, then it appears that they did not get UHC’s EMR system — at least not in terms of what they exfiltrated.

DataBreaches.net reached out to Vice Society to see what they had to say about the incident. One of the questions put to them concerned whether the attack crippled any clinic functioning or services. Their spokesperson responded:

Attack was good but they were lucky. We lost access to some services because something gone wrong )

We can say that they were just lucky =)

Well, UHC may have been lucky in some respects from Vice Society’s perspective, but if Abrams’ source is accurate, UHC was significantly impacted by the attack, and we have already seen that a lot of personal and protected health information is now publicly available. Whether CDPH or HHS will take a deeper dive into why UHC had so much old data unencrypted or not offline remains to be seen. Under HIPAA, entities are required to have risk assessments. Were old data included in UHC’s risk assessment. We may, or may not, find out.

But importantly for now: more than three weeks after when the attack may have occurred and been detected, UHC does not appear to have issued any public warnings to patients that their personal and protected health information has not only been stolen, but made freely and publicly available on the dark web. HIPAA gives entities no more than 60 days from discovery to make notifications to the regulator and patients, but California law only gives them 15 days to notify patients. As a summary of the law by SheppardMullin explains:

Patient Notification. Initially, Section 1280.15 did not specify the content of patient notifications in the event of a breach and only specified that such notice must be provided to affected patients within fifteen (15) days of detection of a breach. The Regulations now provide precise criteria which were largely modeled after HIPAA, and must include a brief description of the breach, a description of the types of information that were involved in the breach, the steps affected individuals should take to protect themselves from potential harm, a brief description of what the covered entity is doing to investigate the breach, mitigate the harm, and prevent further breaches, as well as contact information for the covered entity (or business associate, as applicable).

Could UHC have they mailed everyone already? It’s possible but seems unlikely. This post will be updated when we obtain more information.