Kept in the Dark

Meet the Hired Guns Who Make Sure School Cyberattacks Stay Hidden

This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

This article is published in partnership with WIRED

Schools have faced an onslaught of cyberattacks since the pandemic disrupted education nationwide five years ago, yet district leaders across the country have employed a pervasive pattern of obfuscation that leaves the real victims in the dark, an investigation by The 74 shows.

An in-depth analysis chronicling more than 300 school cyberattacks over the past five years reveals the degree to which school leaders in virtually every state repeatedly provide false assurances to students, parents and staff about the security of their sensitive information. At the same time, consultants and lawyers steer “privileged investigations”, which keep key details hidden from the public.

In more than two dozen cases, educators were forced to backtrack months — and in some cases more than a year — later after telling their communities that sensitive information, which included, in part, special education accommodations, mental health challenges and student sexual misconduct reports, had not been exposed. While many school officials offered evasive storylines, others refused to acknowledge basic details about cyberattacks and their effects on individuals, even after the hackers made student and teacher information public.

The hollowness in schools’ messaging is no coincidence.

That’s because the first people alerted following a school cyberattack are generally not the public nor the police. District incident response plans place insurance companies and their phalanxes of privacy lawyers first. They take over the response, with a focus on limiting schools’ exposure to lawsuits by aggrieved parents or employees.

The attorneys, often employed by just a handful of law firms — dubbed breach mills by one law professor for their massive caseloads — hire the forensic cyber analysts, crisis communicators and ransom negotiators on schools’ behalf, placing the discussions under the shield of attorney-client privilege. Data privacy compliance is a growth industry for these specialized lawyers, who work to control the narrative.

The result: Students, families and district employees whose personal data was published online — from their financial and medical information to traumatic events in young people’s lives — are left clueless about their exposure and risks to identity theft, fraud and other forms of online exploitation. Told sooner, they could have taken steps to protect themselves.

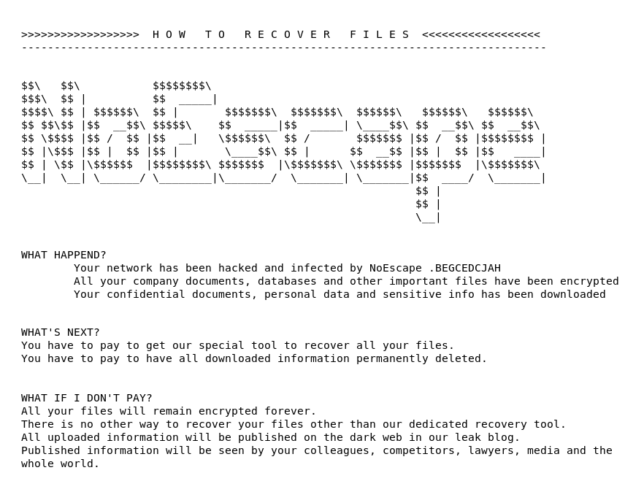

Similarly, the public is often unaware when school officials quietly agree in closed-door meetings to pay the cybergangs’ ransom demands in order to recover their files and unlock their computer systems. Research suggests that the surge in incidents has been fueled, at least in part, by insurers’ willingness to pay. Hackers themselves have stated that when a target carries cyber insurance, ransom payments are “all but guaranteed.”

In 2023, there were 121 ransomware attacks on U.S. K-12 schools and colleges, according to Comparitech, a consumer-focused cybersecurity website whose researchers acknowledge that number is an undercount. An analysis by the cybersecurity company Malwarebytes reported 265 ransomware attacks against the education sector globally in 2023 — a 70% year-over-year surge, making it “the worst ransomware year on record for education.”

Daniel Schwarcz, a University of Minnesota law professor, wrote a 2023 report for the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology criticizing the confidentiality and doublespeak that shroud school cyberattacks as soon as the lawyers — often called breach coaches — arrive on the scene.

“There’s a fine line between misleading and, you know, technically accurate,” Schwarcz told The 74. “What breach coaches try to do is push right up to that line — and sometimes they cross it.”

When breaches go unspoken

The 74’s investigation into the behind-the-scenes decision-making that determines what, when and how school districts reveal cyberattacks is based on thousands of documents obtained through public records requests from more than two dozen districts and school spending data that links to the law firms, ransomware negotiators and other consultants hired to run district responses. It also includes an analysis of millions of stolen school district records uploaded to cybergangs’ leak sites.

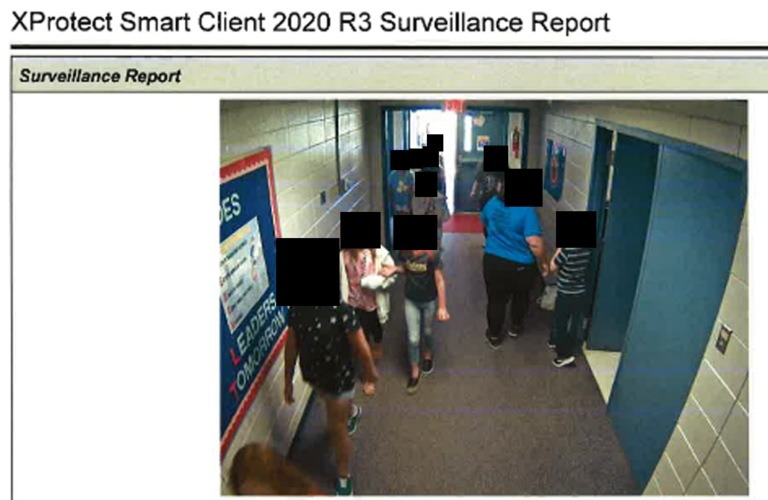

Some of students’ most sensitive information lives indefinitely on the dark web, a hidden part of the internet that’s often used for anonymous communication and illicit activities. Other personal data can be found online with little more than a Google search — even as school districts deny that their records were stolen and cyberthieves boast about their latest score.

The 74 tracked news accounts and relied on its own investigative reporting in Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Providence, Rhode Island and St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, which uncovered the full extent of school data breaches, countering school officials’ false or misleading assertions. As a result, district administrators had to publicly acknowledge data breaches to victims or state regulators for the first time, or retract denials about the leak of thousands of students’ detailed psychological records.

In many instances, The 74 relied on mandated data breach notices that certain states, like Maine and California, report publicly. The notices were sent to residents in these states when their personal information was compromised, including numerous times when the school that suffered the cyberattack was hundreds, and in some cases thousands, of miles away. The legally required notices repeatedly revealed discrepancies between what school districts told the public early on and what they disclosed to regulators after extensive delays.

Some schools, meanwhile, failed to disclose data breaches, which they are required to do under state privacy laws, and for dozens of others, The 74 could find no information at all about alleged school cyberattacks uncovered by its reporting — suggesting they had never before been reported or publicly acknowledged by local school officials.

Education leaders who responded to The 74’s investigation results said any lack of transparency on their part was centered on preserving the integrity of the investigation, not self-protection. School officials in Reeds Spring, Missouri, said when they respond “to potential security incidents, our focus is on accuracy and compliance, not downplaying the severity.” Those at Florida’s River City Science Academy said the school “acted promptly to assess and mitigate risks, always prioritizing the safety and privacy of our students, families and employees.”

In Hillsborough County Public Schools in Tampa, Florida, administrators in the nation’s seventh-largest district said they notified student breach victims “by email, mail and a telephone call” and “set up a special hotline for affected families to answer questions.”

Hackers have exploited officials’ public statements on cyberattacks to strengthen their bargaining position, a reality educators cite when endorsing secrecy during ransom negotiations.

“But those negotiations do not go on forever,” said Doug Levin, who advises school districts after cyberattacks and is the co-founder and national director of the nonprofit K12 Security Information eXchange. “A lot of these districts come out saying, ‘We’re not paying,’” the ransom.

“All right, well, negotiation is over,” Levin said. “You need to come clean.”

Confidentiality is king

The paid professionals who arrive in the wake of a school cyberattack are held up to the public as an encouraging sign. School leaders announce reassuringly that specialists were promptly hired to assess the damage, mitigate harm and restore their systems to working order.

This promise of control and normality is particularly potent when cyberattacks suddenly cripple school systems, forcing them to shut down for days and disable online learning tools. News reports are fond of saying that educators were forced to teach students “the old-fashioned way, with books and paper.”

But what isn’t as apparent to students, parents and district employees is that these individuals are not there to protect them — but to protect schools from them.

The extent to which this involves keeping critical information out of the public’s hands is made clear in the advice that Jo Anne Roque, vice president of risk services account management at Poms & Associates Insurance Brokers, gave to leaders of New Mexico’s Gallup-McKinley County Schools after a 2023 cyberattack.

The district had hired Kroll, which conducts forensic investigations and intelligence gathering. Contracting with a privacy attorney was also necessary, Roque wrote, to shield Kroll’s findings from public view.

“Without privacy counsel in place, public records would be accessible in the event of an information leak,” she wrote in an email to school leaders that was obtained by The 74 through a public records request. School districts routinely denied The 74’s requests for cyberattack information on the very same grounds of attorney-client privilege.

Records obtained by The 74 reveal Gallup-McKinley officials never notified the school community, state regulators or law enforcement about the attack, even after threat actors with the Hunters International ransomware gang listed the New Mexico district on its leak site in January 2024.

In California’s Sweetwater Union High School District, administrators told the public at first that a February 2023 attack was an “information technology system outage” — and then went on to pay a $175,000 ransom to the hackers who encrypted their systems. The payoff didn’t stop the leak of data for more than 22,000 people, nor did the district’s initially foggy phrasing allay public suspicion for very long.

During a March 2023 school board meeting, angry residents accused Sweetwater of being misleading and cagey. One, Kathleen Cheers, questioned whether lawyers or public relations consultants had advised school leaders to keep quiet.

“What brainiac recommended this?” asked Cheers, who wanted the district to create a presentation within 30 days outlining how the breach occurred and who “recommended the deceitful description.”

It wasn’t until June 2023 — four months after the attack — that Sweetwater notified thousands of people their records were compromised. But the district’s breach notice never says what specific records had been taken, refers to files that “may have been taken” and tells those receiving the notice that their “personal information was included in the potentially taken files.”

“Well, was my information taken or not?” April Strauss, an attorney representing current and former employees in a class action lawsuit against Sweetwater, asked The 74.

Strauss, whose clients are also suing the Las Vegas district in a similar lawsuit, accused school officials of downplaying cyberattacks “to avoid exacerbating their liability, quite frankly,” in a way that prevents families from being able to “assert their rights more competently.”

Districts’ vaguely worded breach notification letters to victims serve more to confuse than inform, she said.

“The wording in notices is disheartening,” Strauss told The 74. “It’s almost like revictimization.”

Who’s in charge

Such hedged language used in required breach notices echoes the hazy descriptions districts give the public right after they’ve been hacked. Cyberattacks were called an “encryption event” in Minneapolis; a “network security incident” in Blaine County, Idaho; “temporary network disruptions” in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and “anomalous activity” in Camden, New Jersey.

In several cases, consultants advised educators against using words like “breach” and “cyberattack” in their communications to the public. Less than 24 hours after school officials in Rochester, Minnesota, discovered a ransom note and an April 2023 attack on the district’s computer network, they notified families but only after accepting input from the public relations firm FleishmanHillard.

“ ‘Cyberattack’ is severe language that we prefer to avoid when possible,” the firm’s representative wrote in an email obtained by the Post Bulletin.

The district called it “irregular activity” instead.

In cases where schools are being attacked, threatened and extorted by some of the globe’s most notorious cybergangs — many with known ties to Russia — federal law enforcement officials have claimed several recent victories in arresting and indicting some of the masterminds. Yet The 74 identified instances where police took a secondary role.

In positioning themselves at the helm of cyberattack responses, attorneys have advised districts they should contact law enforcement only “in conjunction with qualified counsel.”

In some cases, including one involving the Sheldon Independent School District in Texas, insurers have approved and covered costs associated with ransom payments, often harder-to-trace bitcoin transactions that have come under law enforcement scrutiny.

Biden’s Deputy National Security Advisor Anne Neuberger, writing in an October op-ed in the Financial Times, said insurers are right to demand their clients install better cybersecurity measures, like multi-factor authentication, but those who agree to pay off hackers have incentivized “payment of ransoms that fuel cyber crime ecosystems.”

“This is a troubling practice that must end,” she wrote.

Records obtained by The 74 show that in Somerset, Massachusetts, Beazley, the school district’s cybersecurity insurance provider, approved a $200,000 ransom payment after a July 2020 attack. The insurer also played a role in selecting other outside vendors for the district’s incident response, including Coveware, a cybersecurity company that specializes in negotiating with hackers.

If police were disturbed by the district’s course of action, they didn’t express it. In fact, William Tedford, then the Somerset Police Department’s technology director, requested in a July 31 email that the district furnish the threat actor’s bitcoin address “as soon as possible,” so he could share it with a Secret Service agent who “offered to track the payment with the hopes of identifying the suspect(s).”

But he was quick to defer to the district and its lawyers.

“There will be no action taken by the Secret Service without express permission from the decision-makers in this matter,” Tedford wrote. “All are aware of the sensitive nature of this matter, and information is restricted to only [the officers] directly involved.”

While ransom payments are “ethically wrong because you’re funding criminal organizations,” insurers are on the hook for helping districts recover, and the payments are a way to limit liability and save money, said Chester Wisniewski, a director at cybersecurity company Sophos.

“The insurance companies are constantly playing catch-up trying to figure out how they can offer this protection,” he told The 74. “They see dollar signs — that everybody wants this protection — but they’re losing their butts on it.”

Similarly, school districts have seen their premiums climb. In a 2024 survey of education leaders by the nonprofit Consortium for School Networking, more than half said their cyber insurance costs have increased. One Illinois school district reported its premium spiked 334% between 2021 and 2022.

Many districts told The 74 that they were quick to notify law enforcement soon after an attack and said the police, their insurance companies and their attorneys all worked in concert to respond. But a pecking order did emerge in the aftermath of several of these events examined by The 74 — one where the public did not learn what had fully happened until long after the attack.

When the Medusa ransomware gang attacked Minneapolis Public Schools in February 2023, it stole reams of sensitive information and demanded $4.5 million in bitcoin in exchange for not leaking it. District officials had a lawyer at Mullen Coughlin notify the FBI. But at the same time school officials were refusing to acknowledge publicly that they had been hit by a ransomware attack, their attorneys were telling federal law enforcement that the district almost immediately determined its network had been encrypted, promptly identified Medusa as the culprit and within a day had its “third-party forensic investigation firm” communicating with the gang “regarding the ransom.”

Mullen Coughlin then told the FBI that it was leading “a privileged investigation” into the attack and, at the school district’s request, “all questions, communication and requests in connection with this notification should be directed” to the law firm. Mullen Coughlin didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Minneapolis school officials would wait seven months before notifying more than 100,000 people that their sensitive files were exposed, including documents detailing campus rape cases, child abuse inquiries, student mental health crises and suspension reports. As of Dec. 1, all schools in Minnesota are now required to report cyberattacks to the state but that information will be anonymous and not shared with the public.

One district took such a hands-off approach, leaving cyberattack recovery to the consultants’ discretion, that they were left out of the loop and forced to issue an apology.

When an April 2023 letter to Camden educators arrived 13 months after a ransomware attack, it caused alarm. An administrator had to assure employees in an email that the New Jersey district wasn’t the target of a second attack. Third-party attorneys had sent out notices after a significant delay and without school officials’ knowledge. Taken by surprise, Camden schools were not “able to preemptively advise each of you about the notice and what it meant.”

Other school leaders said when they were in the throes of a full-blown crisis and ill-equipped to fight off cybercriminals on their own, law enforcement was not of much use and insurers and outside consultants were often their best option.

“In terms of how law enforcement can help you out, there’s really not a whole lot that can be done to be honest with you,” said Don Ringelestein, the executive director of technology at the Yorkville, Illinois, school district. When the district was hit by a cyberattack prior to the pandemic, he said, a report to the FBI went nowhere. Federal law enforcement officials didn’t respond to requests for comment.

District administrators turned to their insurance company, he said, which connected them to a breach coach, who led all aspects of the incident response under attorney-client privilege.

Northern Bedford County schools Superintendent Todd Beatty said the Pennsylvania district contacted the federal Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency to report a July 2024 attack, but “the problem is there’s not enough funding and personnel for them to be able to be responsive to incidents.”

Meanwhile, John VanWagoner, the schools superintendent in Traverse City, Michigan, claims insurance companies and third-party lawyers often leave district officials in the dark, too. Their insurance company presented school officials with the choice of several cybersecurity firms they could hire to recover from a March 2024 attack, VanWagoner said, but he “didn’t know where to go to vet if they were any good or not.”

He said it had been a community member — not a paid consultant — who first alerted district officials to the extent of the massive breach that forced school closures and involved 1.2 terabytes — or over 1,000 gigabytes — of stolen data.

“We were literally taking that right to the cyber companies and going, ‘Hey, they’re finding this, can you confirm this so that we can get a message out?’ ” he told The 74. “That is what I probably would tell you is the most frustrating part is that you’re relying on them and you’re at the mercy of that a little bit.”

The breach coach

Breach notices and other incident response records obtained by The 74 show that a small group of law firms play an outsized role in school cyberattack recovery efforts throughout the country. Among them is McDonald Hopkins, where Michigan attorney Dominic Paluzzi co-chairs a 52-lawyer data privacy and cybersecurity practice.

Some call him a breach coach. He calls himself a “quarterback.”

After establishing attorney-client privilege, Paluzzi and his team call in outside agencies covered by a district’s cyber insurance policy — including forensic analysts, negotiators, public relations firms, data miners, notification vendors, credit-monitoring providers and call centers. Across all industries, the cybersecurity practice handled 2,300 incidents in 2023, 17% of which involved the education sector — which, Paluzzi noted, isn’t “always the best when it comes to the latest protections.”

When asked why districts’ initial response is often to deny the existence of a data breach, Paluzzi said it takes time to understand whether an event rises to that level, which would legally require disclosure and notification.

“It’s not a time to make assumptions, to say, ‘We think this data has been compromised,’ until we know that,” Paluzzi said. “If we start making assumptions and that starts our clock [on legally mandated disclosure notices], we’re going to have been in violation of a lot of the laws, and so what we say and when we say it are equally important.”

He said in the early stage, lawyers are trying to protect their client and avoid making any statements they would have to later retract or correct.

“While it often looks a bit canned and formulaic, it’s often because we just don’t know and we’re doing so many things,” Paluzzi said. “We’re trying to get it contained, ensure the threat actor is not in our environment and get up and running so we can continue with school and classes, and then we shift to what data is potentially out there and compromised.”

A data breach is confirmed, he said, only after “a full forensic review.” Paluzzi said that process can take up to a year, and often only after it’s completed are breaches disclosed and victims notified.

“We run through not only the forensics, but through that data mining and document review effort. By doing that last part, we are able to actually pinpoint for John Smith that it was his Social Security number, right, and Jane Doe, it’s your medical information,” he said. “We try, in most cases, to get to that level of specificity, and our letters are very specific.”

Targets in general that respond to cyberattacks without the help of a breach coach, according to a 2023 blog post by attorneys at the firm Troutman Pepper Locke, often fail to notify victims and, in some cases, provide more information than they should. When entities over-notify, they increase “the likelihood of a data breach class action [lawsuit] in the process.” Companies that under-notify “may reduce the likelihood of a data breach class action,” but could instead find themselves in trouble with government regulators.

For school districts and other entities that suffer data breaches, legal fees and settlements are often among their largest expenses.

Law firms like McDonald Hopkins that manage thousands of cyberattacks every year are particularly interested in privilege, said Schwarcz, the University of Minnesota law professor who wonders whether lawyers are necessarily best positioned to handle complex digital attacks.

In his 2023 Harvard Journal report, Schwarcz writes that the promise of confidentiality is breach coaches’ chief offering. By elevating the importance of attorney-client privilege, the report argues, lawyers are able to “retain their primacy” in the ever-growing and lucrative cyber incident-response sector.

Similarly, he said lawyers’ emphasis on reducing payouts to parents who sue overstates schools’ actual exposure and is another way to promote themselves as “providing a tremendous amount of value by limiting the risk of liability by providing you with a shield.”

Their efforts to lock down information and avoid paper trails, he wrote, ultimately undermine “the long-term cybersecurity of their clients and society more broadly.”

Who gets hurt

School cyberattacks have led to the widespread release of records that heighten the risk of identity theft for students and staff and trigger data breach notification laws that typically center on preventing fraud.

Yet files obtained by The 74 show school cyberattacks carry particularly devastating consequences for the nation’s most vulnerable youth. Records about sexual abuse, domestic violence and other traumatic childhood experiences are found to be at the center of leaks.

Hackers have leveraged these files, in particular, to coerce payments.

In Somerset, Massachusetts, a hacker using an encrypted email service extorted school officials with details of past sexual misconduct allegations during a district “show choir” event. The accusations were investigated by local police and no charges were filed.

“I am somewhat shocked with the contents of the files because the first file I chose at random is about a predatory/pedophilia incident described by young girls in one of your schools,” the hacker alleges in records obtained by The 74. “This is very troubling even for us. I hope you have investigated this incident and reported it to the authorities, because that is some fucked up stuff. If the other files are as good, we regret not making the price higher.”

The exposure of intimate records presents a situation where “vulnerable kids are being disadvantaged again by weak data security,” said digital privacy scholar Danielle Citron, a University of Virginia law professor whose 2022 book, The Fight for Privacy, argues that a lack of legal protections around intimate data leaves victims open to further exploitation.

“It’s not just that you have a leak of the information,” Citron told The 74. “But the leak then leads to online abuse and torment.”

Meanwhile in Minneapolis, an educator reported that someone withdrew more than $26,000 from their bank account after the district got hacked. In Glendale, California, more than 230 educators were required to verify their identity with the Internal Revenue Service after someone filed their taxes fraudulently.

In Albuquerque, where school officials said they prevented hackers from acquiring students’ personal information, a parent reported being contacted by the hackers who placed a “strange call demanding money for ransoming their child.”

Blood in the water

Nationally, about 135 state laws are devoted to student privacy. Yet all of them are “unfunded mandates” and “there’s been no enforcement that we know of,” according to Linnette Attai, a data privacy compliance consultant and president of PlayWell LLC.

All 50 states have laws that require businesses and government entities to notify victims when their personal information has been compromised, but the rules vary widely, including definitions of what constitutes a breach, the types of records that are covered, the speed at which consumers must be informed and the degree to which the information is shared with the general public.

It’s a regulatory environment that breach coach Anthony Hendricks, with the Oklahoma City office of law firm Crowe & Dunlevy, calls “the multiverse of madness.”

“It’s like you’re living in different privacy realities based on the state that you live in,” Hendricks said. He said federal cybersecurity rules could provide a “level playing field” for data breach victims who have fewer protections “because they live in a certain state.”

By 2026, proposed federal rules could require schools with more than 1,000 students to report cyberattacks to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, a division of the Department of Homeland Security. But questions remain about what might happen to the rules under the new Trump administration and whether they would come with any accountability for school districts or any mechanism to share those reports with the public.

Companies that are accused of misleading investors about the extent of cyberattacks and data breaches can face Securities and Exchange Commission scrutiny, yet such accountability measures are lacking for public schools.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, the federal student privacy law, prohibits schools from disclosing student records but doesn’t require disclosure when outside forces cause those records to be exposed. Schools that have “a policy or practice” of routinely releasing students‘ records in violation of FERPA can lose their federal funding, but such sanctions have never been imposed since the law was enacted in 1974.

The patchwork of data breach notices are often the only mechanism alerting victims that their information is out there, but with the explosion of cyberattacks across all aspects of modern life, they’ve grown so common that some see them as little more than junk mail.

Schwarcz, the Minnesota law professor, is also a Minneapolis Public Schools parent. He told The 74 he got the district’s September 2023 breach notice in the mail but he “didn’t even read it.” The vague notices, he said, are “mostly worthless.”

It may be enforcement against districts’ misleading practices that ultimately forces school systems to act with more transparency, said Attai, the data privacy consultant. She urges educators to “communicate very carefully and very deliberately and very accurately” the known facts of cyberattacks and data breaches.

“Communities smell blood in the water,” she said, “because we’ve got these mixed messages.”

Development and art direction by Eamonn Fitzmaurice. Illustrations by Daniel Zender for The 74.

This story was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.