Medical identity theft affected about 1.84 million adults or their family members this year at a projected out-of-pocket cost to the victims of over $12 billion, according to a new report released today.

The Medical Identity Fraud Alliance, with support from ID Experts, recently sponsored a survey conducted by the Ponemon Institute. The researchers surveyed 788 adults who self-reported they or close family members were victims of medical identity theft. Medical identity theft was defined as “when someone uses an individual’s name and personal identity to fraudulently receive medical service, prescription drugs and goods, including attempts to commit fraudulent billing.” The survey posed questions about how the ID theft occurred, the costs of the ID theft, and what steps people took to resolve problems and prevent problems. Some of the key findings, with my analysis and comments incorporated, were:

The number of medical identity theft victims increased last year. The number of new cases over the past year was estimated at 313,000. Extrapolating, the researchers estimate that 1.84 million adults or their family members have become victims this year, significantly more than last year.

Medical identity theft can put victims’ health and lives at risk, yet most consumers do not check their records for medical accuracy. Although 32% of respondents reported no medical consequences, 23% of victims reported that their records were accessed or modified; 15% say they were misdiagnosed when seeking treatment, 14% said there was a delay in receiving treatment, 13% said they received the wrong treatment and 11% say the wrong pharmaceuticals were prescribed. Absent documentation that these occurrences were causally related to the medical identity theft, it is difficult to interpret these data. What is clear, however, is that the majority of those surveyed (56%) reported that they do not check their health records for accuracy. Half of those who do not check their records report that they do not know how to check their records.

56% of medical identity theft victims report they lost trust and confidence in their healthcare provider following the loss of their medical credentials. Given that healthcare providers, their employees, and/or vendors were identified as the source of the breach in only 12% of cases (see Figure 13 below), it would appear that patients lose confidence in healthcare providers even if the incident was not the provider’s fault. As in other studies, the investigators found that 56% of victims say they would find another provider if their provider informed them that their records were lost or stolen. Unfortunately, the survey did not ask how many of the 788 victims actually did leave or change providers following medical ID theft where the provider was – or was not – responsible for the data theft or misuse.

Medical identity theft was costly for over one third of victims. Although 45% of respondents did not suffer any financial consequences in terms of healthcare insurance premium increases, loss of coverage, or gaps in coverage, 7% did experience increased premiums and 34% incurred costs for medical services and medications because of lapse in healthcare coverage, with 18% spending from $5,000 to over $100,000 in out-of-pocket costs for medical services and medications due to the lapse in coverage. Significantly, 43% made out-of-pocket payments to their health plan or insurer to restore coverage. Additionally, 40% of victims reported they reimbursed healthcare providers for services provided to imposters. In 4% of cases, victims paid over $25,000.

Unfortunately, it is not clear whether the patients were actually obligated legally to make those payments or if they just elected to make them for fear of other consequences (such as discovery that they had fraudulently lent their identity information to a family member). The data do suggest, however, that most people do not pay when they become victims. As Dr. Larry Ponemon commented to PHIprivacy.net, those unreimbursed costs must be absorbed by insurance companies, healthcare providers and, they believe, ultimately the taxpayer.

Although two-thirds of the sample reported no costs in trying to resolve the medical identity theft, over one third of victims reported often-significant costs: 26% of the sample reported spending $10,000 – $50,000 just for identity protection, credit reporting and legal counsel. Overall, 36% of victims paid an average of $18,660 to resolve an incident of medical identity theft.

Based on their extrapolation, the researchers estimate the total out-of-pocket costs incurred by medical identity theft victims in the United States will be $12.3 billion this year.

Strikingly, 39% of medical identity theft victims in the sample lost their health insurance coverage as a result of the theft of their information.

The majority of cases of medical identity theft were caused by the victims knowingly sharing their credentials with a family member or friend (30%) or a family member using their information without their knowledge or consent (28%):

The fact that 30% of the sample represented what I would refer to as self-inflicted problems by knowingly lending their credentials to someone who would seek medical care or government benefits poses a number of questions. Would it be accurate to say that 30% of medical identity theft is not really identity theft but willful fraud or conspiracy that comes back to bite the individual by altering their medical records or incurring costs that may cost them their insurance? Perhaps. That statistic – and the fact that another 28% of the sample represents what I would refer to as “familial identity theft” – may help explain why medical ID theft victims are reluctant to report the incidents to the police and reluctant to attempt to resolve incidents.

In response to my questions as to whether the 30% who knowingly lent their credentials to others should truly be considered medical ID theft victims, Dr. Ponemon responded:

Since starting the research on medical identity theft four years ago, we always had a certain percentage of victims who reported that they believed the fraud was committed after sharing their credentials. As part of our first debriefing process when we completed the data collection, we contacted the following: identity theft experts, law enforcement and the FTC. They validated that these people should be included in the sample of victims. Despite sharing credentials and appearing to be a co-conspirator, the conclusion was that law enforcement still considers these individuals victims and their responses are valid. That is why we continue to include this response in the survey instrument each year.

To test the effect the 30 percent has on the results, we did an analysis of the responses without the 30 percent of “sharing victims” included. This resulted in a very slight or no statistical difference in the findings.

Dr. Ponemon’s last statement is somewhat counter-intuitive. I would expect that those who conspired to defraud healthcare providers by lending their credentials and those whose relatives stole their credentials would be significantly less likely to report having become a victim and would be significantly less likely to attempt to resolve the theft for fear of repercussions. My hypothesis is somewhat supported by another finding:

Most cases of medical identity theft are not reported. 57% of respondents did not report the crime. When asked why, the most frequent explanations were that the victim knew the thief and did not want to report them (48%) or because they did not think the police would be of any help (50%).

Most cases of medical identity theft do not involve financial or credit card fraud for victims. Only 12% of the sample responded that their information was stolen to obtain fraudulent credit card accounts. Inspection of the data suggests that none of the victims in this sample had been victims of tax refund fraud or had been notified by the IRS or law enforcement that their data had been misused. Given how prevalent tax refund fraud and Medicare fraud by providers has become, this finding is somewhat unexpected. In discussing this with Dr. Ponemon, we considered the possibility that the definition of “medical identity theft” and the screening tool to identify survey participants may have eliminated victims who should have been included, such as patients whose information was stolen for tax refund fraud and not to obtain medical services. If those types of cases were included, the rate of medical ID theft would be even higher than that reported in this survey.

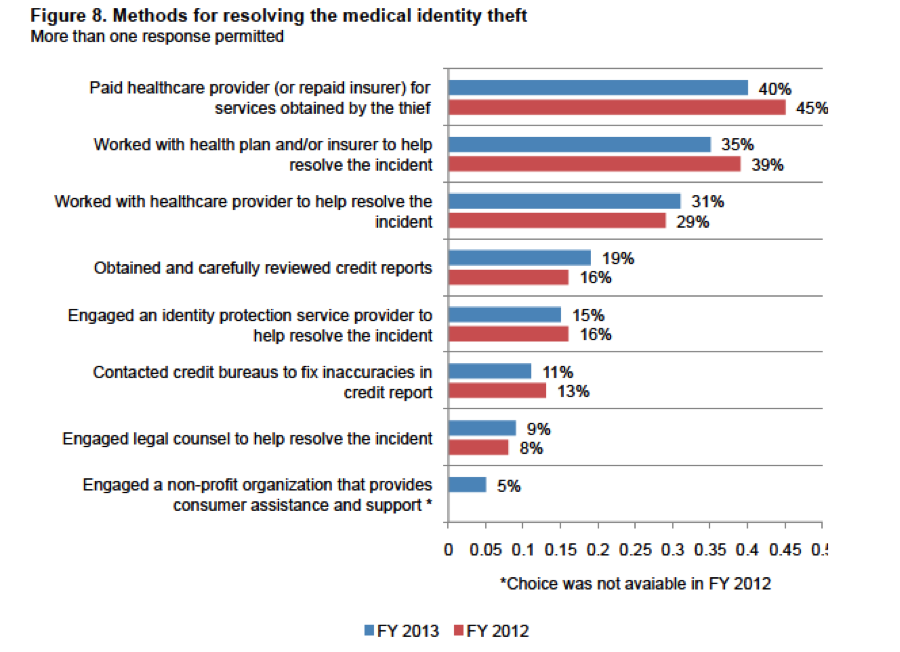

Medical identity theft can take a long time to resolve. Although 50% of the sample made no attempt to clear up the incident (possibly for reasons described above), an additional 29% reported that the incident was resolved within one year, and 11% reported that it had taken more than 2 years and/or wasn’t resolved yet. Forty-five percent reported that they had spent more than 100 hours trying to resolve the incident, and for 45%, it wasn’t resolved yet. Victims used a variety of means to try to resolve the incident:

You can access the full report here (pdf).

The report makes a number of common-sense recommendations as to how consumers can do a better job of protecting ourselves from medical ID theft:

- Review your Explanation of Benefits (EOBs). Ensure the doctors listed and services provided are accurate. If you find an incorrect item, even if no money is owed, contact your insurance company immediately.

- Obtain your “benefits request” annually. Your insurance provider can provide a list of all benefits and services paid in your name, which you can review to confirm all the services listed were received.

- Protect your medical insurance card. Leave your insurance card in a safe place, and don’t carry it with you unless it’s necessary.

- Safeguard your insurance-related paperwork. Shred or file your Explanation of Benefits in a safe, and preferably locked location.

- Report lost or stolen health insurance identification cards. Alert your insurance carrier of misplaced, lost, or stolen cards to avoid unauthorized use.

- Use vigilance when providing your personal or insurance information. Be sure you’re dealing with a reputable healthcare provider. Be cautious when offered free medical services. Often fraudsters use this as a way to obtain your health information.

- Review your credit reports annually. You have a right to request a free annual credit report from each of the three credit bureaus. Be sure your reports are free of any medical liens.

To which I’d add:

Don’t share your health insurance information with family or friends. Not only are you engaging in criminal activity by defrauding providers and insurers, but the costs you incur financially may result in tens of thousands of dollars in bills that can hurt your health insurance and/or credit rating. It’s nice that you want to help your family or friends, but this is not the way, and:

If you don’t know how to read an EOB, call your insurance carrier and ask them to go through it with you.

Finally, the survey results – and those of their previous surveys – raise a number of policy questions, including:

1. Should victims of medical identity theft perpetrated by others without their consent or active involvement have protection so that they do not have to repay healthcare providers or insurers for services provided to the identity thieves?

2. Have Red Flag rules had any significant impact on reducing identity theft in the healthcare sector, or do other steps need to be implemented?

3. Are breach notification laws (HITECH and state laws) having any appreciable effect on reducing medical identity theft? With recent changes in HITECH’s threshold for notification, we expect to see more notifications in situations where entities might not have notified before. Will that lowered threshold help prevent medical ID theft? We’ll have to wait for data on that.

***

Figures in this post are used with the permission of Ponemon Institute.