As I’ve lamented (ok, bitched) many times: trying to notify an entity of a privacy or data security concern can be time-consuming and frustrating if the entity does not provide a clear means to notify them or doesn’t respond to your e-mails or calls. If you are thinking of trying to notify Maricopa County, Arizona of any concern, you may want to pack a picnic lunch. Definitely pack lots of coffee.

This privacy advocate/journalist’s latest episode of “What Do We Have to Do to Get a Response from You?” was triggered by thousands of Form 1099-INT and Form 1099-MISC tax statements that were exposed and freely available on the county’s anonymous public FTP server. A Form 1099-INT includes the recipient’s name, address, a truncated Social Security number (SSN) or Tax Identification Number (TIN) and the amount of interest income paid to the individual or entity during the year. A Form 1099-MISC is used for non-wage miscellaneous compensation. It includes the recipient’s name, address, identification number (truncated SSN, or individual tax identification number, or employer identification number), and the amount of compensation paid.

The tax statements, exposed on Maricopa County’s FTP server, had been indexed by Google and Filemare. A search for “1099-MISC” had revealed their availability. No login was required if one simply clicked on the search results links. And that’s exactly what a security researcher tells DataBreaches.net that he did.

The researcher’s analysis revealed that there were four unencrypted files available on the server:

- A 1099-INT file from 2015-2016 with 860 tax statements

- A 1099-MISC file from 2015-2016 with 263 tax statements

- A 1099-INT file from 2014 with 1,027 tax statements, and

- A 1099-MISC file from 2014 with 455 tax statements

All told, the files contained 2,605 tax statements, 1,479 of which included individuals’ truncated SSNs. Anyone searching the individuals’ names in Google would also find their 1099 from Maricopa County.

As the researcher commented, with the information in the forms, criminals could aggregate other information, socially engineer or phish individuals for additional details, and either scam them or engage in identity theft:

“Identity thieves are like bloodhounds. if you give them a hint of personal information, they can use the limited amount of information to seek out and discover the pieces that are missing, until a fully fleshed-out profile of their mark is uncovered.”

Rick Kam, Co-Founder and President of ID Experts, agrees that the exposed files might increase the risk of identity theft, telling DataBreaches.net:

“I would say it potentially increases the risk of identity theft since the last 4 digits of SSN are used to identify people at many financial services companies. The risk of spear phishing attacks increases and the potential for this data being combined with other stolen credentials increases the risk.”

Although the exposure does not appear to be a reportable breach under Arizona’s breach notification statute, and the tax statements might be public records under Arizona law [a point I’ve been unable to confirm so far], their ready availability was still concerning.

Did Maricopa County intend for those tax statements to be available to the entire world on an anonymous FTP server? We don’t know because they have not responded to any inquiries, but they should have been aware that anything in the Special.Downloads folder could be accessed and downloaded by any member of the public, as the README file on the server makes clear (emphasis added):

Anonymous public access allows the public to place files in the Put.To.Maricopa directory. They will only be able to list files placed in this directory during their session. They can retrieve files from Get.From.Maricopa/Normal.Downloads and Get.From.Maricopa/Special.Downloads.

And so it began….

Not knowing whether the availability of these tax statements was by design or by error, both the researcher and this blogger attempted to alert the county to the issue. The researcher attempted to notify Maricopa County of the situation by e-mail on June 22, but received no response. Yours truly made several phone calls the next day to different departments, including the Treasurer’s Office, Human Resources, and the Office of Enterprise Technology. The latter transferred me to an employee in customer service for their IT Department, who agreed to take a detailed message and forward it to their IT security personnel. But hours went by, and the files were still unsecured, so I e-mailed the county’s media team, told them what was going on, and urged them to contact their IT security people promptly. But by Wednesday evening, the files were still unsecured and no one had replied to any of the voicemails or emails. By Thursday morning, the files had been secured, but they remained available in Google and Filemare cache.

Did the fact that Maricopa removed or secured the files mean that they had been exposed in error, or did it mean that after hearing from this reporter, they had a change of heart about making them so easily available? I had no idea, and no one contacted me at all to explain.

I contacted the media team again, asking for a statement explaining why these tax statements had been on an anonymous FTP server and who was responsible for securing them. In response, they informed me that when they had gotten my previous e-mail, they had contacted the office responsible for the server, as it was an elected office that they did not work for. And what was that elected office, I asked them? I received no response to that question, despite a second request via e-mail. And I received no answer to any of the other questions I had posed to them.

By 5 days after we began trying to notify them, other than the one response from their communications team, no one from Maricopa County ever responded.

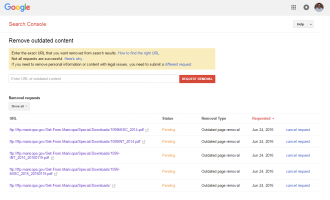

On June 24, despite not even getting an acknowledgement of his previous attempt to help them, the researcher attempted to get Google to remove its cached copies of the files:

DataBreaches.net does not know if Maricopa County had initiated any such rapid removal request, but it would seem that the researcher cared more about protecting individuals than the county did. By Sunday afternoon, the cached copies had been deleted.

Maricopa County’s Mixed Record on Infosecurity

In addition to the concern about having these statements on an anonymous public server and failing to respond to those trying to notify them of the risk, there was also a third concern raised by this incident. The continued presence of records from 2014 in the “Special Downloads” folder clearly violated the county’s policies and procedures. According to the “README” file on the server (emphasis added):

Get.From.Maricopa/Special.Downloads – Files can only be placed in this directory by designated department FTP administrators. These are considered temporary files and will be purged after 15 calendar days. Upon request the file may be moved to Get.From.Maricopa/Normal.Downloads by the Telecommunications Administrator.

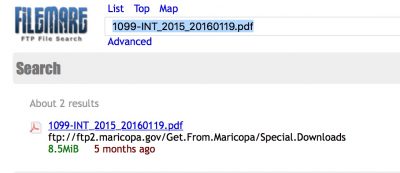

Purged after 15 calendar days? That obviously didn’t happen, as Filemare shows that the most recent file had been uploaded 5 months ago:

Presumably, the 2014 files were uploaded even longer ago.

Who in Maricopa County was responsible for purging those files? And who was responsible for oversight of that?

Maricopa County’s checkered history on data security

In November, 2013, this author reported that Maricopa County Community College District (MCCCD) had suffered the largest data breach ever reported in the education sector. Nearly 2.5 million students, former students, vendors and employees were notified that their name, birth date, Social Security numbers and bank account information had been exposed. Compounding the problem, it took MCCCD seven months after they were informed of their breach by the FBI to notify everyone – even though some data had reportedly been found up for sale on the dark web.

This reporter’s subsequent investigation revealed that the 2013 breach was MCCCD’s second data breach in as many years, with the second breach being just a vastly larger version of a 2011 breach that had never been fully remediated. In the process of trying to defend itself against the outrage the 2013 breach triggered, MCCCD blamed the breach on employees who had tried to get MCCCD to address the uncured 2011 breach. Heads rolled, but it wasn’t management’s heads that rolled. The 2013 breach resulted in a number of class action lawsuits that ultimately settled. It also resulted in MCCCD paying $26 million or more in attorneys’ fees, consultant fees, and measures to improve their infosecurity.

But it wasn’t just MCCCD experiencing serious infosecurity failures. Other Maricopa County entities had also had a long history of infosecurity problems, and the concerns raised by this 1099 situation are consistent with a report issued by the state’s Office of the Auditor General for the year ended June 30, 2015 which found a number of deficiencies.

Yet other criticisms of Maricopa County’s infosecurity were evident in an April 25, 2016, Security Scorecard article on their ranking of 600 government entities, where Maricopa ranked the worst among local governments they had assessed in February, 2016:

While SecurityScorecard’s measures are likely somewhat idiosyncratic, being the worst of the worst on any comparative infosecurity assessment is generally not a Good Thing.

Interestingly, SecurityScorecard’s negative report on Maricopa was issued only months after Maricopa County won a leadership and innovation award for the progress it had allegedly made in infosecurity over the past few years.

So which is it? Is Maricopa County a shining light when it comes to infosecurity at the county level, or is it the poster child for inadequate security and poor incident response? It is likely somewhere in-between.

Hopefully, the county will see this commentary and tweak its incident response plan to make notification a less time-consuming and frustrating process for those who are taking time out of their busy days to try to alert them to concerns about protecting personal information. If the files were available by design as public records, it would only have taken a quick e-mail or call to say, “Thanks for your concern, but those are public records and they are supposed to be available.” Or if they weren’t supposed to be there, to say, “Thanks for alerting us. We’ve now secured the files.” Seriously: how hard would that have been, Maricopa?

Update: Post-publication, I received a response from the state as to whether 1099 forms are disclosable public records. The answer was not definitive, but here is part of it:

The default position in Arizona is that public records are available upon request; however, there are three general situations in which public records can/must be withheld. The first is when a record is made confidential by statute. The other two are when the agency at issue determines that a privacy or State interest outweighs the public’s right to see the record.

Again, I am not especially knowledgeable when it comes to tax information, but I think that at least some of the information in these statements is rendered confidential by federal statute. For instance, pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §405(c)(2)(C)(viii)(I), “Social security account numbers and related records that are obtained or maintained by authorized persons pursuant to any provision of law enacted on or after October 1, 1990, shall be confidential,and no authorized person shall disclose any such social security account number or related record.”

So to answer your questions:

First, no, I do not think these tax statements “need to be provided unredacted to requestors.” Social security numbers, at least, must be redacted. It is quite possible (or even likely) that federal or State law or rules prohibits the disclosure of more information on these forms, if not the entire forms. Even if federal and State law or rules do not expressly prohibit the disclosure of this information, counties would be able to make good arguments that the contractors’ privacy interests in their personal information outweighs the public’s right to see much of it.

[…]

Good write up!

Thank you. Would that they had responded as quickly as you do!

I have contacted insider in neighboring county, awaiting response on whether they can break thru the communication breakdown.