More than 40 million Iranians had their personal data leaked and shared with strangers because they tried to use an alternative to Telegram after their government banned its use. It’s time for Iran to lift the ban before there are more massive leaks as people go online to seek information about COVID-19.

by Dissent Doe with Under The Breach

A recent report by Comparitech and Bob Diachenko concerning an exposed elasticsearch server with data scraped from a forked Telegram app was one of numerous leak reports during March. The leak had exposed data of more than 42 million Iranians, and by the time Comparitech published their report on it, some of the data had already appeared for sale on a hacking forum.

Another day, another leak, right? We don’t think so. It turns out that this leak has multiple layers to it and serious implications for not just those immediately impacted by the leak, but for human rights in Iran. So let’s take another look at what we do know about this incident.

On March 29, Under The Breach, a data breach monitoring and prevention service tweeted about a listing on a forum offering 40 million Iranians’ telephone data:

Actor selling information about 40,000,000 million Iranians which appear to originate from @Telegram.

– Data includes names, phone numbers, usernames, photos, last seen.

– I verified the data by importing the phone numbers to Telegram as contacts, usernames match. pic.twitter.com/kSz2Zm2MKE— Under the Breach ? (@underthebreach) March 29, 2020

Later that day, @underthebreach revised his assessment a bit, tweeting:

The names don’t appear to match the data from Telegram, they possibly originate from a different source.

I hope it isn’t espionage by the Iranian government.

— Under the Breach ? (@underthebreach) March 29, 2020

His concern about possible government spying would later appear to be well-founded.

The next day, Comparitech and Bob Diachenko reported finding what appears to have been the same exposed elasticsearch instance. They report that the data had been posted by a group called “Hunting system” (translated from Farsi). As @UndertheBreach had suggested the previous day when he found the data were not consistent with Telegram, Comparitech reported that a Telegram spokesperson informed them that the data appeared to come from forked Telegram apps.

As with so many other elastic search leaks we have seen, although the system did require credentials in order to log in, the backend of the service which contained all the information was completely exposed for everyone to see (i.e., the server was open on Port 9200).

Underthebreach’s tweets and Comparitech’s report resulted in a number of Iranians becoming furious and determined to find out who was collecting the data and who was responsible for failing to secure it.

[NOTE on the translation above: The tweet actually talks about 40 million and not 5 million. Running it through a translator yields this version: “Apparently, someone is selling the information of 40 million Iranians, including name, phone number, half user, photo, and so on. Data is probably one of the unofficial telegrams. Will any of our claimants put pressure on these informal telegrams why their information is being sold in this way?

Use formal programs”]

Outraged Iranians on Twitter even started a hashtag to express their anger and concern: #سامانه_شکار (for Hunting System). But they did more than just create a hashtag. Iranians are technologically savvy and they used some solid OSINT to discover who is behind the exposed server.

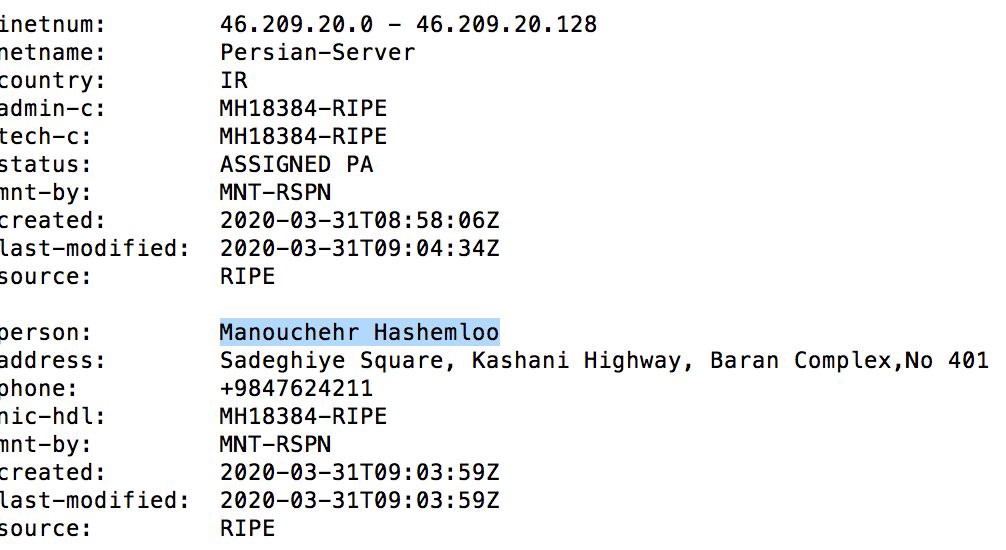

First they examined the block of IPs in the range of the exposed server (46.209.20.26) and found that they belong to “persian-server,” hosted by Manouchehr Hashemlou.

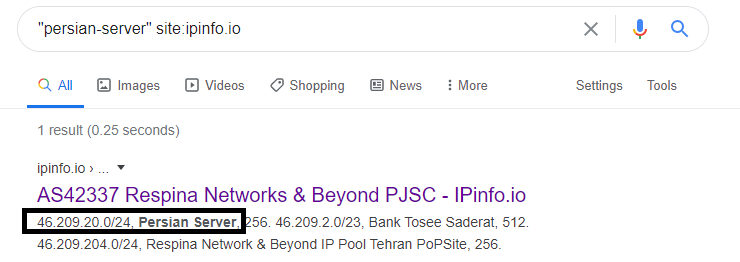

Note that the listing depicted above shows the netname as “Persian-Server.” After the public became aware of the leak and started tweeting about it, the netname was mysteriously changed to “Respina.”

Further investigation revealed that Hashemloo’s name was also linked to “Mahanserver,” which subsequently changed names to Ariadc. Ariadc is a data center registered by [email protected].

Aryaieiran had been discussed by ClearSky in a 2017 report about the APT group known as Charming Kitten, and they had found a number of connections between him and Black Hat Turk and other Iranian hacking groups, but what was Aryaieiran doing in 2020 seemingly running a server designed for mass social media scraping? Was this evidence that Iran was spying on its citizens by collecting data on those who registered for a forked version of Telegram? Was Charming Kitten engaging in domestic spying for the state? Was Aryaieiran just acting on his own outside of any state or group affiliation (as Charming Kitten member Behzad Mesri is thought to have done when he hacked HBO to extort them over Game of Thrones)? Or did Aryaieiran have nothing to do with the scraped data at all? But if this was all innocent, why was the netname registration changed to replace “Persian-Server” with “Respina” shortly after the leak became public? And was it significant that the group was called “Hunting System?” Does the “hunting” refer to hunting dissidents?

In response to some questions DataBreaches.net posed to them, Charles Carmakal of FireEye informed this site that they have been tracking Aryaieiran since 2013 as a member of a number of hacking teams on a number of Iranian hacking forums. They are also currently investigating infrastructure that may be tied to him.

So it appears that Aryaieiran may still be very active and may be acting in ways tied to domestic spying activities.

In any event, the public outrage on Twitter about the leak and concerns as to whether the state might be involved were picked up by Amir Nazemy, Head of the Information Technology Organization of Iran, who forwarded it for judicial review.

Iranian CERT issued a statement, but then deleted it shortly thereafter. Their statement (translation) did not appease many people.

It’s a Matter of Human Rights

As a matter of human rights, governments should not ban apps that citizens use to obtain news or exchange information — even if that information is unflattering to the government. As a matter of human rights, governments should not put people in the position of having to choose between violating a government ban and using apps or services that are more likely to have privacy or security failures.

This leak is partly a direct result of Iran’s government trying to prevent its citizenry from unfiltered access to news and exchange of opinions. By banning Telegram in response to dissidents who had some protection using end-to-end encryption in messaging, the government left its people with limited choices: either learn to use proxies and VPNS to access Telegram or use forked versions of Telegram that may not have the high level of security that Telegram provides.

Under The Breach informs this site that from the limited data available to him, he was unable to determine if the exposed data all came from Holgram or Talagram, the two most used forked versions of Telegram in Iran (https://en.radiofarda.com/a/iran-telegram-app-circumvention-domestic-apps/29365779.html). Comparitech obtained a statement from Telegram stating “that the data seems to have originated from third-party forks extracting user contacts. Unfortunately, despite our warnings, people in Iran are still using unverified apps. Telegram apps are open source, so it’s important to use our official apps that support verifiable builds.”

At a Time of Crisis, Iran Must Stop Censoring News and Its People

This incident represents much more than just sloppy security on a forked version or unverified build, though. This incident is a cautionary tale of what happens when a government tries to censor the public from obtaining news and sharing ideas.

We are in the midst of a global pandemic. Now, more than ever, we all need access to accurate scientific and health information about COVID-19 and what we can do to protect ourselves and others. The government of Iran should immediately lift the ban on its citizens’ use of Telegram because access to information and news is now a genuine matter of life or death. Iranians should not have to risk massive breaches of their personal information because they are trying to communicate with others during these difficult times.

This article was corrected post-publication to correct the misspelling of Charles Carmakal’s name.