More than two years after he was extradited from the Czech Republic where he was arrested in 2016 for hacking LinkedIn, Dropbox, and Formspring, Russian national Yevgeniy Nikulin was sentenced today to 88 months by Judge William Alsup in federal court in northern California.

Nikulin, also known as “Chinabig01,” “dex.007, ” “valeriy.krutov3, and “itBlackHat,” had been charged with three counts of computer intrusion, two counts of damaging a protected computer, two counts of aggravated identity theft, one count of conspiracy, and one count of trafficking in unauthorized access devices for the hacks that occurred in 2012.

The 33 year-old Russian national was convicted in July in a jury trial that was delayed due to the pandemic. Evidence introduced at trial showed that Nikulin had hacked into a LinkedIn employee’s account and had installed malware on it that allowed him to establish remote control over the computer, which he then used to steal LinkedIn users’ login information. He used the same approach with DropBox and Formspring. Nikulin had been accused of stealing roughly 117 million usernames and passwords, which he then sold to others on Russian-language forums.

Nikulin’s connection to other Russian hackers and individuals who might be politically connected or connected to the government has never been fully explained publicly, including why Russian diplomats visited Nikulin in jail on multiple occasions without his lawyer present. Mike Eckel provides other intriguing details in his report earlier today.

In its presentencing filing, the government, represented by David L. Anderson, Michelle Kane, and Katherine Wawrzyniak, sought a sentence of 145 months plus three years supervised release, plus restitution.

Defense counsel for Nikulin, who put on no defense during trial after the prosecution rested, took the approach of asking the court to sentence Nikulin to time served and to send him back to Russia. The defense argued that both LinkedIn and Dropbox had significantly inflated the amount of loss they had sustained and the court should not use those figures in calculating sentencing. They argued that Nikulin, now 33 and with a 10 year-old daughter in Russia by his first wife, had already been in custody (in the Czech Republic during the extradition battle and then in the United States from March, 2018) for a total of 48 months already.

Apart from disputing the amount of loss the victims experienced, Nikulin’s lawyers, Adam Gasner and Valery Nechay, argued for a reduction in sentencing due to defendant characteristics:

i. Age

ii. Family ties and responsibilities

iii. Lack of youthful guidance

iv. Mental and emotional condition

v. Non-violent offender

vi. Physical condition

All of these factors can reduce a sentence, and the lawyers provided letters from Nikulin’s mother, his ex-wife, his brother, his step-father, and his 10-year-old daughter. Some of the letters attested to the abuse and psychological problems Nikulin had reportedly suffered, beginning as a young child being physically abused by his biological father. They also pointed out the significant impact the suicide of his older brother had on him, and how much his family and daughter missed him and how they would make sure to get him the psychiatric help he needs. Some of the filings also claimed that Nikulin had medical and dental issues that had not been treated appropriately during his time in custody, although (and not surprisingly) investigation by the U.S. claimed that he received timely and appropriate treatment for all of his dental and medical complaints.

Nikulin’s possible psychiatric issues have come up on numerous occasions following his arrest and extradition. Those issues may not have elicited any sympathy from those who may have seen pictures of him posing with his Lamborghini or staying in a posh hotel on vacation.

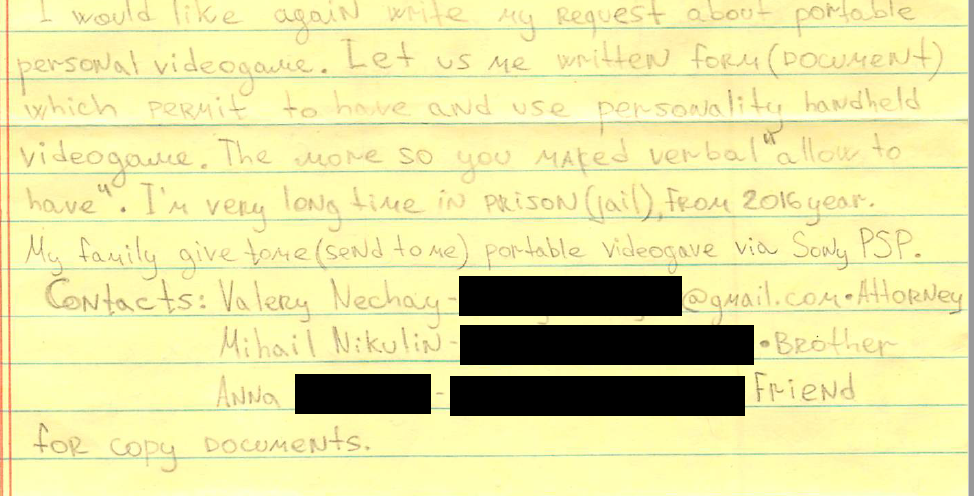

Related to that point, nowhere in their filings did I see even any hint that Nikulin experienced or expressed any remorse for what he had done. Nikulin seemed to reserve his regret for what he had done to his family. And he seems to have saved his greatest sympathy for himself, writing to the judge on multiple occasions to request access to the PSP system his family had sent him.

In response to defense motions that had been filed and that Judge Alsup denied — a motion for acquittal and a motion for a new trial — Judge Alsup began by commenting that although he had commented publicly at several points during the trial that the government’s case had seemed disjointed and possibly too weak to go to jury, the government’s closing argument, which he described as one of the best he had ever heard in 21 years, tied everything together and made him understand that this was not a weak case, but a very strong case. He also used the opportunity to compliment the defense counsel who he said did an “admirable job — they played the cards they were dealt in the best possible way.” This was a case, though, he said, where the prosecution benefitted from the trial and the defense didn’t. Had Nikulin pleaded guilty, the judge might have sentenced him to time served. But the more he got to know about him from the trial, the more serious he understood this to be.

With motions denied, the hearing turned to sentencing and the only real objection by the defense, which concerned the amount of loss difference. Nikulin’s defense attorney, Adam Gasner, tried to point out discrepancies in what LinkedIn had claimed at different points and the absence of evidence supporting specific loss claims. His presentation was interesting because he emphasized that not one person had ever come forward to claim that he had become a victim of identity theft or fraud from these hacks, and that therefore, although it is certainly worrying to be notified of this type of breach, where is there any evidence of “loss?” Judge Alsup pushed back on that noting that his sympathies were with the common people who are just trying to get by, and now have this additional worry to deal with. The judge said he’s not sure it’s “loss,” but it is “multiplied by millions of people and that has to count for something.”

The government responded to the defense’s alternate loss calculation and sentencing application. They reminded the court of what one Formspring employee had testified about the amount of time he had to spend dealing with the compromise of his account, and how that would apply to the millions of people whose credentials had been compromised.

On rebuttal, Gasner was clear that although LinkedIn claimed $2 million in loss, they had never provided any documentation showing any costs. Yet for the court to accept that $2 million loss claim would raise the sentencing level by 16 levels, which is significant. Gasner noted that if any individual had made that claim, the court surely would have asked to see proof. For LinkedIn to say that they were unable to provide any documentation of costs associated with the breach yet have Nikulin sentenced on supported claims like that is unfair to the defendant.

Nikulin’s other attorney, Valery Nechay, then turned to other factors or variances that impact sentencing, starting with childhood abuse that began when his mother was still pregnant with him. He began having documented problems in childhood and in adolescence that were exacerbated by the suicide of his older brother, who had adult-onset schizophrenia that had not been diagnosed promptly. Nikulin has himself been diagnosed as recently as last year with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, conversion hysteria, and psychosis, among other issues, and continues to have manic episodes, according to his attorney. He has suffered so much, she argued, that it would be a deterrent to him ever doing anything like this again.

In rebuttal, the government noted that some of his diagnoses had been disputed, but even though the government couldn’t confirm or refute claims about childhood abuse, the court had seen evidence of him with his friends and girlfriend and on social media, and he appeared to be fully functioning. And if his relatives point out that he was a loving father, then he was functioning successfully despite all the alleged issues and problems.

What seemed to bother the judge the most was the possibility that Nikulin, if returned to Russia, would return to hacking and he would be out of the U.S. jurisdiction with no extradition agreement with Russia. The judge asked about his family’s ability to visit him even though the government counsel noted that he had regular phone contact with his relatives.

And finally, the government pointed out what I had also noted — that Nikulin has never taken responsibility or expressed any remorse for the consequences of his behavior. And of course, the government wants the court to send a message to hackers that would be a deterrent to others.

Judge Alsup appeared to be conflicted by the possibility that he was not getting adequate medical care here and that he was all alone, with no family visiting him here and limited in his communication skills, with no one else in the jail who speaks his language.

When given the opportunity to make a statement, Nikulin declined the opportunity to address the court.

For sentencing purposes, Judge Alsup noted that the probation report noted this was a nonviolent crime (Category 1) with offense level 32. For that, the sentencing guidelines are in the range of 121-151 months. The government sought 145, and the defense wanted time served (48 months).

Judge Alsup noted that although this was a nonviolent crime, it was a very serious crime that impacted many people, and it is a hard crime to track down overseas and extradite the perpetrator, making it a more severe crime. And the distance may make criminals feel immune from prosecution, so the courts have to send a stiffer sentence to let criminals know that if they do get caught, there will be serious consequences.

The Judge agreed with the defense’s claim that LinkedIn’s loss claim may have been exaggerated, but “common sense” dictates that they did experience significant loss. Based on that, he reduced the level one step from 16 to 14. At that level (30), the sentencing range becomes 97-121, and that’s the range he used.

Even that range is very severe, the judge noted, in light of COVID-19 which makes being in prison now “harder time” than it would have been two years ago. It’s also harder for Nikulin because he is in a country that he didn’t want to be in and speaks no English. “It’s not quite Kafkaesque,” he said, “because he did the crime, but it is harder on him than it is on the ordinary defendant.” It’s also harder, the judge noted, because Nikulin’s mother probably won’t live to see him come out of prison, and that makes his time even harder.

While showing sympathy for Nikulin in some respects, Judge Alsup discounted the childhood issues and most of the variances, noting that Nikulin was functioning well enough to hack and be driving around Bentleys, etc. He described Nikulin as almost a genius, who, he believes, poses a substantial risk of recidivism.

More than one and half hours after the sentencing hearing started, Judge Alsup announced his sentence that he believes is consistent with the lowest level that meets the objectives of Congress in setting the guidelines: 88 months. That includes a 24-month sentence added for aggravated identity theft that has to be run consecutively after other charges. The court also imposed a term of three years of supervised release if he is not deported from this country immediately after his sentence is completed. On release, he will likely be deported and will not be under conditions of U.S. supervision.

The sentence also included restitution, including but not limited to $1 million to LinkedIn and $514,000 to Dropbox.

Updated to Explain: While Nikulin was sentenced to 88 months, he will (only) serve another 26 months or so at this point. Because defendants have to serve 85% of the sentence, that would be 74.8 months. He gets credit for time in custody in the Czech Republic and the U.S., which is about 48 months (I don’t have the exact figure right now). So that leaves him with 26.8 months of incarceration to serve.

Can you please fix a rather glaring error. There is no such country as Czechoslovakia. There are two countries – Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Ugh. Old habits die incredibly hard. Thank you.